The last of the Mackie Brothers of Tarves, sadly has passed away. George, brother to Lord John and Sir Maitland (Snr) was born on the family farm in Tarves (Ythsie). George, had a long career in farming, business, the military and politics.

Commenting, Local Councillor Paul Johnston said: “George made his name elewhere, farming in Angus and being MP for Caithness and Sutherland, but his roots were Tarves and round about. He is remembered in old photos in the Methlick Scouts. His Brothers Maitland and John, also gone, will be joined by that larger than life figure. I met ‘Benshie’ as a young Liberal and he was great charecter at conferences. A sharp mind, like all in his family, his passing away marks the end of one era of Mackies. He will long be remembered in many different circles.”

The Guardian has run an obituary which we reproduce below.

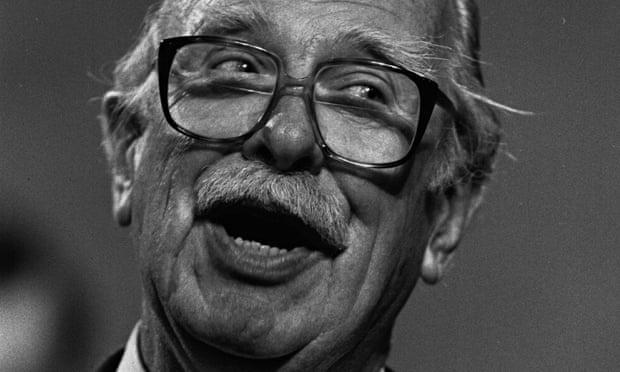

Lord Mackie of Benshie obituary

George Mackie, Lord Mackie of Benshie, a Liberal Democrat peer and the former Liberal MP for Caithness and Sutherland, who has died aged 95, was a striking figure in more ways than one. Besides standing 6ft 4in in his socks, he was a war hero, having survived three operational tours – more than 70 missions – with Bomber Command in the second world war. He picked up a DFC and the DSO along the way.

George was essentially a farmer and at the outbreak of war, he was a trainee farm manager in East Anglia. When he returned six years later, he set up on his own account with a uniquely beautiful farm called Benshie, in Angus. He made a great great success of it, using the profits to start a cattle ranch at Braeroy, near Ben Nevis, and then to buy a glass factory and a hotel in what became his parliamentary constituency in the far north of Scotland.

Born on the family farm at Tarves, Aberdeenshire, to Maitland Mackie, and his wife, Mary (nee Yull), George was the fifth of six children, born on the family farm at Tarves. He demonstrated the physical courage that made him a war hero quite early in life. All six children went to the local village school. John, the eldest, was sent off on his first day wearing a Mackay tartan kilt. He returned from the school bruised and scratched, having been mercilessly teased, tore off the kilt and declared he would never wear it again. Next up was Mike, and the same thing happened. So when George followed on, the rest of the family waited breathlessly to see what would occur. When George came home he too was bruised and scratched. But he said nothing, kept on his kilt, and ate his tea in stoical silence. When one of his sisters asked: “Were you not teased about your kilt, George?” he replied tersely: “Just once.” Next morning he returned to the school in his kilt. No more was heard of the matter.

When war was declared in 1939, George went straight off and volunteered for the RAF and in order to get in more quickly, he agreed to join as an observer/navigator rather than as a pilot, something he always regretted. But, as he remarked in his autobiography, Flying, Farming and Politics (2004), he enjoyed the war, which was just as well, because he had a lot of it.

It began in Britain, then shifted to Egypt, and then back to the UK again for the great bomber offensive against German cities. In spite of the huge civilian casualties, George never had a moment’s doubt about the rightness of this offensive, arguing that it forced Hitler to shift a massive amount of arms production from offensive weapons for fighting the Russians to anti-aircraft weapons to defend Germany. He remained convinced that it made a major contribution to the eventual Soviet triumphs in the east, describing it as a de facto “second front”.

He took a similar view of the very heavy casualties that Bomber Command suffered during the offensive. In George’s squadron, only seven out of 30 crews survived their first operational tour of 25 raids. Between October 1943 and May 1944, it was losing about one crew a week. In these circumstances it was difficult but absolutely essential to maintain morale. By then a squadron leader in charge of a flight of Lancaster bombers, George had a big role in this task and he admitted that drink had a large part in keeping the tension down. Many beery nights were spent in the Cutter Inn in Ely, near 115 Squadron’s Cambridgeshire base. George used to say that its landlady made a major contribution to the war effort by looking after 115 Squadron’s airmen so well.

It was in that pub that he celebrated the award of his DSO. His former girlfriend in Aberdeen, Lindsay Sharp, saw the announcement in the Aberdeen Press and Journal and wrote to congratulate him. He wrote back and the affair was resumed, and Lindsay started travelling to Ely to visit him. They got engaged in March 1944, when George was approaching the end of his third operational tour.

The next move was to London and the Air Ministry, but not before he had married Lindsay. The couple settled in London at the height of the German doodlebug offensive and just as the V2 rocket attacks were beginning. But eventually the war ended, and its ending on 7 May 1945 happened to be the day on which the Mackies’ first child was born.

While he waited to be demobilised, George’s father was hunting for a farm for him. The two of them settled on Benshie, which was not only fine farming land but also had a beautiful house with a beautiful view over Strathmore, in Angus. He moved into the farm even before he left the RAF, just in time to vote Liberal in the 1945 election. That in itself was quite surprising, because George had previously been a Labour supporter. He seems to have been influenced by Jo Grimond, later a Liberal MP and the party’s leader, and joined the Liberal party in 1949. In the 1959 election, he stood as the (unsuccessful) candidate in South Angus.

After that election, Grimond was the only Liberal MP in Scotland. His party numbered just six in the Commons – a state of affairs that led to jokes about it being possible to cram the entire Liberal party into a London taxi. But about this time it emerged that infighting had developed in the Conservative party in the Tory-held constituency of Caithness and Sutherland in the far north of Scotland. Grimond suggested that the Tories could be beaten and that George should go for the Liberal candidature. He did, but secured the local party’s nomination by only one vote.

George won the seat narrowly. His brother John was already in the Commons as Labour MP for Enfield, and had been appointed junior minister for agriculture in Harold Wilson’s 1964 Labour government. One of the entertainments of that short-lived parliament was George, as Liberal spokesman on agriculture, badgering his brother John at agriculture question time.

But Wilson, who had won the 1964 election with a majority of only three, was forced to go to the country again less than two years later. This time Labour had got its act together in Caithness and George was beaten by 64 votes. He set about consolidating the many business enterprises he had either bought or set up in the north.

They included not only the glass factory and a dairy but two hotels, one at John O’Groat’s and the other perched on the edge of the Pentland Firth at Tongue. The latter became a Good Food Guide choice in what was otherwise a culinary desert. In 1974 he was offered a life peerage, which (as he put it) he “grabbed”. When his brother John arrived as a Labour peer, the entertaining jousts between them resumed.

In 1985 Lindsay contracted leukaemia, and died, a devastating blow. In 1988 George married Jacqui, the widow of Andrew Lane, the Dundee hotelier who had been his partner in running the Tongue hotel. He retired from farming soon afterwards, and Benshie was sold. Eventually the couple bought a smaller house at Oathlaw, not far from the old farm. They called it Benshie Cottage, and were still living there until George’s death.

His life had been coloured by the war and and like many other participants in that terrible conflict, the experience made him a passionate believer in European unity. Much of his political life was devoted to that idealistic concept, including membership of the Council of Europe and a brief spell in the European parliament before it became a directly elected body. He spent many years on House of Lords committees charged with examining EU legislation.

George is survived by Jacqui, by his three daughters, Lindsay, Jeannie and Diana, by seven granddaughters and by four great-grandchildren. He was predeceased by a son who died in infancy.

• George Yull Mackie, Lord Mackie of Benshie, politician and farmer, born 10 July 1919; died 17 February 2015